INTRODUCTION

In the early hours of March 14, Ghana experienced a nationwide internet outage that caused unimaginable disruption, crippling our daily life. The two largest telecommunication companies, which accounted for over 70% of the market share, lost data connectivity. Several hours later, information crept in – the problem was caused by damaged submarine cables (also referred to as undersea cables) located off the coast of Côte d’Ivoire! The outage badly impacted Ghana and other neighbouring countries as the telcos rely heavily on these submarine cables to deliver internet and data access. Internet service was gradually restored to most users after three long days, leaving the country largely offline for days.

During this period, many activities ground to a halt – people could neither use ride-hailing apps to get around nor access banking services. Internet-based entertainment and communication that has become the norm was lost, with many left confused and unsure of how to occupy their time or undertake essential activities. This incident brought home forcefully to everybody the importance of understanding where their internet connectivity is coming from, particularly the reliance on undersea cables. The ramifications of a compromised submarine cable network are telling and far-reaching – going beyond mere inconvenience to encompass matters of economic resilience, national security and vulnerabilities of a network that the modern world is highly dependent on.

The contribution of the telecommunication sector to government revenue, and economic development generally, in Ghana is substantial. The Ghana Chamber of Telecommunications, for example, reported a remarkable increase in tax payments in 2022, with the industry contributing over GH¢6 billion in taxes and other payments. This figure represented approximately 8.02% of the government’s tax revenue for that year, emphasising the sector’s substantial economic footprint. Submarine cables are susceptible to natural and human-made threats, thus, regulators, industry players, policymakers and stakeholders must prioritize the protection of the submarine cable network. Collaborative efforts (both regional and international) are necessary, and this should be bolstered by strategic investments in infrastructure resilience and security measures. The consequences of inaction are too dire and scary to contemplate, with the potential for widespread disruption and chaos looming on the horizon.

“When communication networks go down, the financial services sector does not grind to a halt,…it snaps to a halt”

Stephen Malphrus,

Chief of Staff to Federal Reserve Chairman, USA

SUBMARINE CABLE NETWORK

The submarine cable network is a vital infrastructure underpinning the global exchange of information. These cables, buried deep beneath the ocean’s surface enable the transmission of vast amounts of telecommunications data across continents. They transmit terabits of data per second, dwarfing that of satellite services in comparison. Approximately 97% of all telecommunication and internet data flows through these submerged conduits, making them critical to global commerce, communication, and innovation. Submarine cables are primarily financed by consortia of firms or tech giants like Google, Meta, Microsoft, and Amazon. According to the World Economic Forum, these tech companies possess or lease roughly 50% of the cables worldwide.

The high costs of constructing these cables and their private ownership have resulted in governments playing a less active role in transnational communications infrastructure compared to other strategic industries.

The global submarine cable network has undergone remarkable development since its inception in the late 19th century. The laying of submarine cables is inherently capital-intensive and has historically relied on ships for installation. The successful laying of the first transatlantic cable in 1866 marked the beginning of this network, expanding into a comprehensive global telegraphic cable network by 1900, with the transpacific connections completed two years later. The transition from telegraphic to telephonic cables occurred in 1956 with the inauguration of the first transatlantic telephone line (TAT-1). The bandwidth limitations persistently made transoceanic communication costly and primarily utilized for commercial or governmental purposes. Further technological development led to the laying of the first transatlantic fiber-optic cable (TAT-8) in 1988.

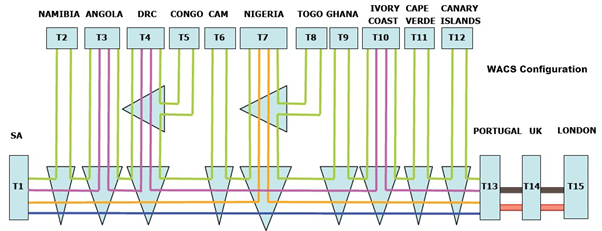

Over the subsequent years, fiber optic cables proliferated worldwide, facilitating connectivity between economies and societies and laying the foundation for the Internet as we know it today. Unlike earlier point-to-point cable installations, technological advancements in branching allowed a single cable to serve multiple hubs, such as those in Africa and Latin America. The global submarine cable network is designed with redundancy as a fundamental principle. For example, major connections such as transatlantic and transpacific routes, feature multiple parallel cables, ensuring that a failure in one cable can be mitigated by rerouting traffic through others. The West Africa Cable System (WACS) is a submarine communications cable that plays a crucial role in connecting South Africa to the United Kingdom along the western coast of Africa. Formerly known as the Africa West Coast Cable (AWCC), WACS spans approximately 14,530 kilometers and comprises four fiber pairs. The cable system features 14 landing points, encompassing 12 locations along the African coast, including Cape Verde and the Canary Islands, with additional landing points in Portugal and England. The construction of WACS, facilitated by Alcatel-Lucent, involved a huge investment of $650 million.

Source: Submarine Cable Network

WACS, designed to enhance regional connectivity and global telecommunications, contributes tremendously to data and communication transmission services across 15 countries. The cable system’s design capacity initially stood at 5.12 Tbps, leveraging advanced technology to support high-speed data transmission. Over time, upgrades have further boosted WACS’s capabilities, with the Huawei Marine upgrades carried out in 2015 and 2019, raising the system’s design capacity to 14.5 Tbps.

There are other cable network that serve Ghana and othe countries and three of them are of interest because th they were damaged alongside WACS in the 14 of March incident. Theseare; the South Atlantic-3/West Africa Submarine Cable (SAT-3/WASC), which links South Africa to Europe via West Africa, the MainOne network which connects countries including Nigeria, Ghana, and Ivory Coast, and the African Coast to Europe (ACE) cable network. ACE links Portugal to the West African coast, encompassing countries like Morocco, Mauritania, and Senegal.

Source: Africa Undersea Cables

SAFETY AND SECURITY OF SUBMARINE CABLES

Submarine cables are faced with various threats – potential risks to their safety and security. These include accidental damage resulting from fishing trawlers dragging nets along the seafloor, anchor drops from large vessels, construction or repair work near landing sites, and underwater natural disasters like earthquakes and turbidity currents. There is also the danger of deliberate damage through acts of terrorism, sabotage, or extortion. The threat profile is summarized below:

Statistically, fishing vessels pose the greatest threat to submarine cables because of their trawl operations. It is estimated that 50-100 incidents of disruptions are associated with fishing vessels.

Cable faults by cause (1959-2006).

Source: UNEP-WCMC, ICPC

This is particularly, a major threat in West Africa, given the prevalence of fishing vessels in the region and trawling activities. Also high in the threat profile of the region are concerns with offshore oil and gas seismic activities. Therefore, proper monitoring and repair capabilities are required to effectively tackle all such threats.

LEGAL AND REGULATORY FRAMEWORK

The recent internet outage in West Africa has reinforced the need to better understand and critically examine the legal and governance frameworks surrounding submarine cables. It is significant to note that a submarine cable may traverse the high seas, through maritime space(s) under national control before making a landfall. The international community has a governance framework on the rights and duties of states with regard to submarine cables. Key in this regard are the 1884 Convention for the Protection of Submarine Telegraph, and the 1982 United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).

The fundamental legal framework that governs the use of maritime space is UNCLOS. It deals with the rights and responsibilities of states in terms of the freedom to lay, protect, repair and maintain submarine cables. Considering the High Seas, the right to lay submarine cables has been provided as one of the vital freedoms under Article 86 of UNCLOS, while in the case of the deep seabed, it has been outlined in Article 112. Additionally, the Convention guarantees the freedom/right to lay submarine cables in the Exclusive Economic Zone (EEZ) of states (Article 58). Article 79 provides the same freedom in respect of the Continental Shelf – sea floor of states. The contentious issue is whether the exercise of the right to lay a submarine cable in the EEZ or on the Continental Shelf should receive the consent of the coastal state. With or without the expressed approval, the laying of the cables must necessarily have ‘due regard’ for the interest of the coastal state. Unlike the laying of submarine cables in the High Seas, deep seabed, EEZ and continental shelf, the laying of submarine cables in or through the territorial sea of a coastal state has different legal ramifications.

In general terms, the territorial sea refers to the maritime space up to about 12 nautical miles (about 18 kilometres) from the baseline – around the coastline. The territorial sea falls within the sovereignty of the coastal state. Thus, the laying of cables in the territorial sea requires the authorisation of the coastal state and the state equally has the legal authority or responsibility to ensure the protection of the cables and is expected to enact laws to that effect (Article 21).

A close reading of UNCLOS would reveal that it dwells more on the rights and freedoms relating to the laying of submarine cables, with fewer provisions regarding the protection, safety, and security of the cables. An earlier legal regime, governing the protection, safety and security of these cables is the 1884 Convention of Protection of Submarine Cables. It was the first significant milestone that recognized the need to safeguard underwater communication infrastructure. Its objective is to ensure that states enact legislation to safeguard cables located beyond their territorial waters. Some international organisations and institutions also play crucial roles in regulating submarine cables.

The International Telecommunication Union (ITU), the International Cable Protection Committee (ICPC), and the International Standards Organization (ISO) work together to establish technical standards, promote best practices, and coordinate efforts to protect submarine cable infrastructure globally.

ENSURING SUBMARINE PROTECTION AND RESILIENCE IN GHANA

In Ghana, the National Communications Authority (NCA) is the body overseeing the regulation of submarine cables, and the ministerial oversight is provided by the Ministry of Communications. The Electronic Communications Act, 2008 (Act 775), provide licensing requirements for operating submarine cables within the country. Very little exists, however, regarding the protection, safety, and security of submarine cables.

In 2018, the United Nations adopted Resolution 73/124 reaffirming the need for states to adopt requisite legislations, policies, and strategies for the protection of submarine cables.

Ghana and other African countries must hasten to put in place comprehensive legislation governing the laying and protection of submarine cables as well as a resilience framework to address and respond to threats. Ghana and other West African countries should take proactive steps to strengthen protections for their vital submarine cable networks.

As in other areas of governance, safety and security, most states in West Africa, lack the framework for the protection of submarine cables including legislation. This would have to change! Premium should be put on regular inspections and the monitoring of cable routes to help detect any damage in real-time. Also, coastal surveillance and security need to be strengthened through coordinated patrols (surface & aerial) and demarcated barriers along high-risk cable pathways.

Equally vital, is to make sure that there is regional collaboration by way of information sharing on potential threats to preempt disruptions. Working with cable operators to map infrastructure, diversify routes, and educate maritime stakeholders should be the way forward to safeguard assets from both accidental harm and deliberate attacks. If Ghana and her neighbors prioritize the protection of these submarine cables through preventative measures and regional cooperation, it will build resilience of internet connectivity across West Africa in the years ahead. By adopting a proactive and holistic approach, Ghana can effectively mitigate threats to its critical infrastructure and safeguard its national interests. The Ministry of Communications and NCA must not only lead in guaranteeing a robust protection and resilience framework for Ghana but also accept to work in concert with regional states to ensure a region-wide protection and resilience framework.