Background

With the renewed focus on the ocean as essential to the attainment of the global Sustainable Development Goals (SDG), it is no doubt that maritime security governance has been placed at the fore of national agendas of coastal states across the globe. Ghana remains no exception. The surge in piratical attacks in the Gulf of Guinea and the increasing spread of the menace into the maritime domain of Ghana has made the subject of maritime security governance germane. In the past decade, there has been a burgeoning awareness of the host of maritime security concerns that plague Ghana, as well as of their implications for the livelihood and well-being of the populace. Headlines of the country’s fisheries crisis, illegal bunkering, piracy and more recently, thousands of dead fish and over hundred dolphins washed ashore have slowly begun to raise questions about the role of Ghana’s security agencies in safeguarding the country’s maritime domain; and whether or not these roles are being executed efficiently.

These questions point to a conundrum that has long impacted maritime governance in the country. Much like other countries within the West African sub-region, Ghana’s maritime domain is characterised by a large number of actors and stakeholders with linkages in mandates, roles and primary functions. While such an extensive maritime institutional framework could lead to greater functional or sectoral efficiency through harmonised capacities and shared information, the institutional framework suffers from interagency frictions, duplication of efforts and uncoordinated threat responses. Addressing Ghana’s maritime security challenges therefore requires a good understanding, not only of individual institutions and their specific roles within the sector, but also of the interactions between these institutions and the practicalities involved in the interplay of their roles and mandates.

Such discourse can yield benefits for addressing current and evolving maritime security concerns, especially because they require a shift from a problem orientation to a solutions orientation that relies on institutional structures and mechanisms to support maritime security on an ongoing basis. At the sub-regional level, we envisage two primary positives: given the shared nature of the maritime space, interagency coordination within Ghana’s maritime environment would result in enhanced maritime security in Ghana’s waters, with a cascading effect on regional maritime security. Secondly, lessons learnt from practical coordination amongst Ghanaian agencies can be replicated in other countries across the sub-region and further modelled to facilitate collaboration at the regional level.

Interagency Coordination or Something More?

Within the context of governance, interagency coordination encompasses the entire array of efforts and activities amongst two or more agencies, working jointly and contemporaneously to address a common threat, concern or incident. In some cases, it also connotes galvanizing collective capacities for greater progress, attaining unity of efforts or ensuring efficiency and better outcomes. Among maritime stakeholders, there is a tendency to view interagency coordination as an end in itself. However, interagency coordination should not be the ultimate intent in maritime governance, as it often connotes a more reactive posture to maritime security concerns than a proactive one. Rather, agencies must learn to move beyond coordinating activities in response to incidents or threats to active collaboration and cooperation on shared initiatives and to a complete integration of mechanisms that support a layered approach to maritime security governance and synergy of operations.

In the case of Ghana, such a comprehensive approach to advancing maritime governance at the interagency level could involve creating platforms through which stakeholders can actively engage in dialogue, share information on a regular basis, conduct threat assessments and harmonise standards of operations in response to maritime security incidents.

Ghana’s Interagency Cluster – Mapping the Actors & Stakeholders

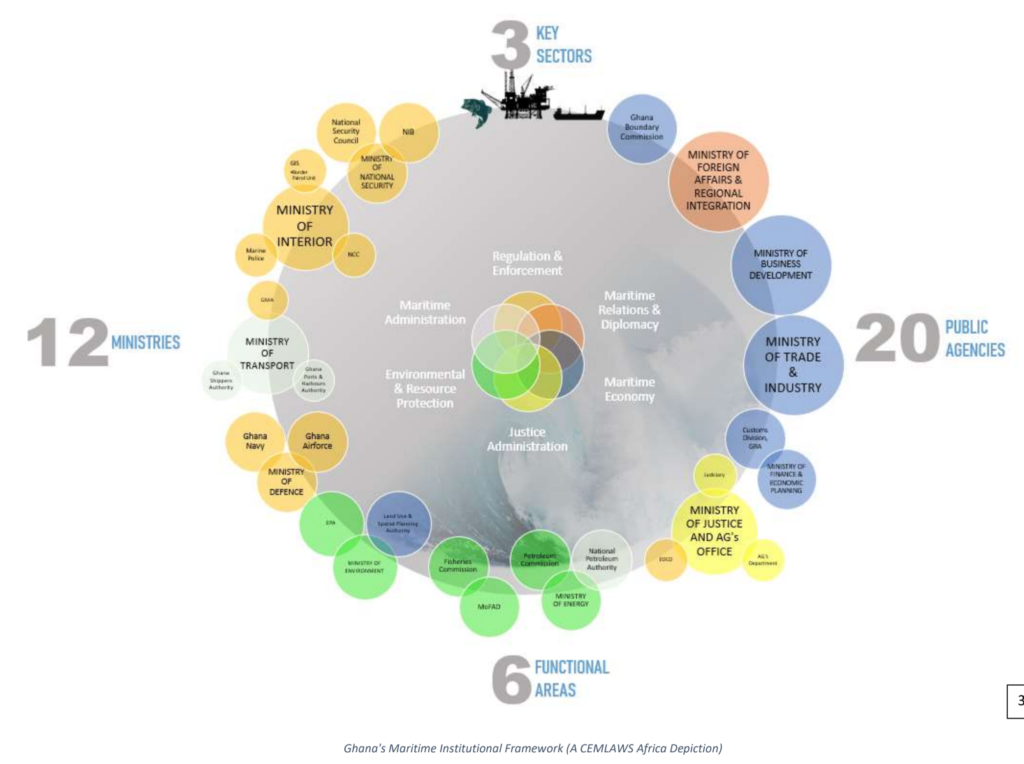

The stakeholders and actors within Ghana’s maritime domain can be mapped on the basis of sectoral units and functional areas. More specifically, three primary sectors have been identified by CEMLAWS Africa as fundamental to Ghana’s blue economy and socio-economic advancement: maritime transport, fisheries and oil and gas sectors. Beyond these sectors, there exist a number of functional areas within which institutions with some form of maritime mandate may operate:

- Regulation and enforcement

- Maritime administration

- Environmental and resource protection

- Justice administration

- Maritime relations and diplomacy

- Marine spatial planning and blue economy

Each of the institutions within Ghana’s maritime governance framework are clustered around these functional areas. In all, there exist twelve (12) ministries and twenty (20) public agencies which play a role in ocean governance and maritime security.

The number of stakeholders highlight one crucial fact: there is a convoluted mix of ministries and agencies within Ghana’s maritime governance framework; and while the figure below depicts only their most dominant functional areas, some of these ministries, as well as their key agencies, have roles to play across two or more functional areas. For instance, the Ministry of Transport has roles

to play in maritime regulation and enforcement, maritime administration, environmental and resource protection and maritime economy. Likewise, the Ministries of Interior and Defence also have such cross-functional roles. While having ministerial oversight and institutional roles across functions is inevitable, it does point to the need for greater efforts toward attaining synergy in maritime governance.

The Problem

Ghana’s maritime interagency cluster may look structured on paper, but the operational complexities of having such an intricate web of institutions go far beyond categorising them on the basis of sectors or functional areas. For instance, there has been a long standing contention as to which agency plays the lead role in Ghana’s maritime security governance; the Ghana Maritime Authority (GMA) or the Navy. Although the primary role of the GMA as stipulated in the GMA Act (Act 630) appears to be one of regulation coordination and monitoring of affairs within Ghana’s maritime industry, the Agency, in practice, has often had to assume a more direct role in maritime security governance. This presents some conflicts or challenges to maritime security governance and can create possible gaps in leadership, or affect the requirement of unity of effort, which is key to delivering effective maritime security.

Towards Effective Interagency Maritime Security Collaboration: A Tool-kit for Ghana?

The large number of ministries and agencies involved in maritime governance in Ghana points to the need for a systemic approach to interagency coordination in the maritime governance architecture, based on set parameters. Any mechanism designed to facilitate beneficial interactions amongst agencies towards the attainment of shared goals must have some vital elements in order to be successful.

In the discussion that follows, we proffer key parameters of interagency coordination with recommendations on enhancing maritime security in Ghana through enhancing synergy amongst existing agencies.

It is important to stress, however, that there is no ‘one size fits all’ nor can the list of parameters or critical requirements be circumscribed to those discussed below.

1. Collaborative Platforms

Collaboration cannot occur in the absence of a suitable platform that permits agencies to converge for the purpose of deliberating on shared concerns. Typically, these platforms can take an array of forms, from boards at one end of the spectrum to working groups or joint task forces at the other end. Institutions in themselves can provide platforms for collaboration, especially where they are established for that fundamental purpose. For instance, Ghana’s National Security Council was established to coordinate policy and responses on shared national security concerns. Thus, it may provide a viable medium for integrating the perspectives and concerns of various stakeholders within the country’s maritime security environment for the purposes of policy formulation and threat response. However, that depends on how maritime security is prioritised within the national security profile of Ghana.

A closer look at Ghana’s maritime security architecture shows that though collaborative platforms may exist, two key problems persist. First, some platforms remain under-utilised, as is the case with the National Security Council in coordinating maritime security dialogue and responses. Secondly, existing interagency platforms are often over-stretched for outcomes that cannot be compressively achieved. This is the case with using the GMA Board as the primary interagency maritime security platform when it is clear that other agencies that are key to effective maritime security are not represented on the Board.

A third limitation on the efficacy of collaborative platforms is the dichotomy between higher level dialogue and follow-up mechanisms for implementing and coordinating decisions and policies. For example, the GMA and Ghana Navy have for many years been collaborating on the GMA Board, but this usually constitutes higher-level dialogue that may not give due consideration to direct operations and coordination concerns of both agencies, which are the most fundamental elements that need to be addressed in fostering interagency coordination and synergy. It was in 2006 that adequate arrangements were made to have a Navy liaison officer deployed to the GMA headquarters to facilitate dialogue between the two institutions.

2. Clear Institutional Mandates/ Adequate Legal Framework

One of the reasons why collaborative platforms may not enhance interagency coordination is lack of clarity on the specific mandates of the agencies involved. The reasons for this uncertainty may be be tri-fold:

- Establishing acts or legal instruments empower institutions to execute very similar (or identical) mandates, without specifying the lead agency

- Establishing acts or legal instruments fail to detail all expected areas in which a specific agency was originally intended to execute its mandate

- Agencies are established or constituted to perform a role without adequate legal backing.

In the context of maritime regulation and enforcement initiatives, the question remains as to whether the GMA should play a lead role on the basis of the empowerment granted to it under the Maritime Security Act 2004 (Act 675) or whether the Ghana Navy, whose primary mandate is to protect and defend the maritime territorial integrity of Ghana, should be considered the lead agency. Again, several of the ministries and public agencies mapped out above have no direct indication of their ocean governance or maritime security roles in their mandates. This is true for institutions such as the National Intelligence Bureau (NIB), Economic and Organised Crimes Office (EOCO) and the Narcotics Control Commission (NACOC), whose role in maritime regulation and enforcement are key.

3. Institutional Capacity

Closely related to the issue of clear mandates is the need to empower stakeholder institutions and build their capacity and capabilities as a means of fostering sound interagency collaboration. Each institution must be adequately equipped to effectively execute its mandate at sea. This may involve ensuring that staff are sufficiently trained on elements of maritime governance, regulation and enforcement applicable to their roles, particularly because well-trained staff would be better equipped to contribute meaningfully to interagency dialogue. It would also involve improving overall institutional capability to address and respond to maritime security incidents. It is worth noting that efforts have been made by the Ministry of Foreign Affairs and Regional Integration (MFARI), Environmental Protection Agency (EPA), Ghana Immigration Service (GIS), Customs Division of the Ghana Revenue Authority (GRA) and Ministry of Justice and Ministry of Justice and Office of the Attorney-General (MoJ-AG) to train selected personnel in relevant aspects of maritime regulation and enforcement. Nonetheless, such efforts have been largely inconsistent, resulting in a persistence of inadequate capacity, with ripple effects on coordination and collaboration.

4. Transparency and Information Sharing

All successful models of interagency coordination and collaboration require functional information sharing mechanisms and institutions that are willing to commit to sharing all relevant information with each other. Recent successes chalked within the Yaoundé Architecture in countering piracy threats and attacks off the Gulf of Guinea are a case in point. There has been a heavy reliance on the ability of regional navies to share information on the nature of on-going attacks, as well as on vessel locations. Unlike some other elements of coordination, information sharing relies substantially on technological capabilities of the agencies involved. As an example, Ghana’s Vessel Traffic Management Information System (VTMIS) includes ten (10) monitoring stations located within various stakeholder agencies. However, technical challenges with the system in agencies such as the National Security Council and Fisheries Enforcement Unit have had grave repercussions for coordinating with the GMA in addressing threats off Ghana’s coasts. As a matter of fact, the monitoring station within the National Security Council has not been operational in at least three (3) years.

5. Accountability

Agencies must be held accountable for executing their maritime mandates effectively. With adequate communication and reporting mechanisms in place, agencies should be able to show measurable outputs that reflect prioritising interagency collaboration over duplication of efforts and unwillingness to share information. Ultimately, this will foster a sense of responsibility and proactivity within Ghana’s maritime governance framework.